“Simplicity is the highest goal, achievable when you have overcome all difficulties. After one has played a vast quantity of notes and more notes, it is simplicity that emerges as the crowning reward of art.”

– Frederic Chopin

As the adrenaline is still pumping, as the denouement fades to black, we are met by the gentle, rhythmic tip tapping of Chopin’s Prelude, Op 28, No. 15, and we are left jarred by the contrast, questioning the intent behind such a welcome but unexpected artistic choice.

What is the significance of this wonderful piece of music? Its calm, pleasant tone doesn’t appear to fit the overall feeling we get from Prometheus. Is it out of place? Or does it tell us something? Well, Chopin could be giving us clues about plot or theme – he could be commenting on the nature of the human mind – or it could simply be an attempt to steady our heart rate after a sensory overload. I’m certain it’s each of those things, since it is a rich, layered composition with a telling story of its own. Although all art originates from deep within the artist’s subconscious mind, Prelude No. 15 is a rare specimen, since we can be quite sure of the source, of its inspiration.

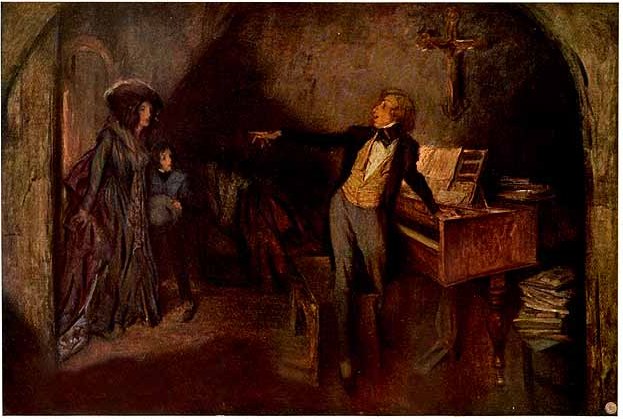

Chopin was suffering from tuberculosis and taking refuge from a miserable Paris winter on the Mediterranean island of Majorca, with his lover, George Sand and her children. A short journey across the island had turned into an odyssey for the mother and her child as an uncharacteristic storm hampered their journey; the composer was alone, at home, and beginning to worry that they might not return. According to Ms Sand, the composition was the product of a nightmare that Chopin had experienced during this stressful time and the sound of the rain, falling rhythmically upon his roof, had infected his thoughts.

“It was there he composed these most beautiful of short pages which he modestly entitled the Preludes. They are masterpieces. Several bring to mind visions of deceased monks and the sound of funeral chants; others are melancholy and fragrant; they came to him in times of sun and health, in the clamour of laughing children under the window, the faraway sound of guitars, birdsongs from the moist leaves, in the sight of the small pale roses coming in bloom on the snow. … Still others are of a mournful sadness, and while charming your ear, they break your heart. There is one that came to him through an evening of dismal rain — it casts the soul into a terrible dejection. Maurice and I had left him in good health one morning to go shopping in Palma for things we needed at our “encampment.” The rain came in overflowing torrents. We made three leagues in six hours, only to return in the middle of a flood. We got back in absolute dark, shoeless, having been abandoned by our driver to cross unheard of perils. We hurried, knowing how our sick one [Chopin] would worry. Indeed he had, but now was as though congealed in a kind of quiet desperation, and, weeping, he was playing his wonderful Prelude. Seeing us come in, he got up with a cry, then said with a bewildered air and a strange tone, “Ah, I was sure that you were dead.” When he recovered his spirits and saw the state we were in, he was ill, picturing the dangers we had been through, but he confessed to me that while waiting for us he had seen it all in a dream, and no longer distinguished the dream from reality, he became calm and drowsy while playing the piano, persuaded that he was dead himself. He saw himself drowned in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water, indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds. He protested with all his might — and he was right to — against the childishness of such aural imitations. His genius was filled with the mysterious sounds of nature, but transformed into sublime equivalents in musical thought, and not through slavish imitation of the actual external sounds. His composition of that night was surely filled with raindrops, resounding clearly on the tiles of the Charterhouse, but it had been transformed in his imagination and in his song into tears falling upon his heart from the sky.”

– George Sand

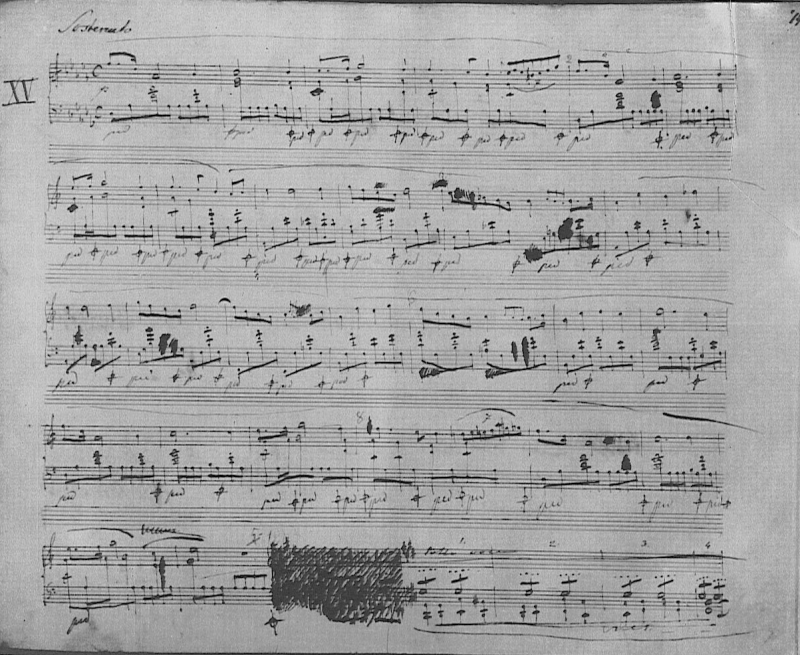

Since it was created under such conditions, with a repeated note appearing throughout, this Prelude is affectionately known as the Raindrop Prelude, or Raindrops. Both beautiful and haunting, poetic and affecting, melancholic in parts, even angry for a short while, it perfectly captures the artist’s state of mind at the time. A soft, gentle opening, that is replayed at the close, frames a dark, dramatic mid-section. Chopin softly doses, then rises into a dark dream state – we feel his pain, we sense his anxiety – before resting peacefully once more.

It’s the absence of this tempestuous middle section within Prometheus that I find most intriguing. The first part of the main theme begins when Shaw’s dream is interrupted by David. It continues while we observe vignettes of the android as he occupies himself ‘alone’ aboard the Prometheus, and only ends once the on-board computer declares “destination threshold”. We have to wait for the final bars of the masterpiece, which are only heard once the blood curdling scream of the recently hatched xenomorph eventually fades into the blackness preceding the credits. The heavy, stirring mid-section of the composition – the dark, chaotic, affecting nightmare that Chopin so eloquently captures in C-sharp minor – is never heard during the film. It is, instead, substituted by the ordeal we vicariously experience during the ill-fated mission undertaken by the Prometheus crew. This is intentional. We are Chopin, drifting off to feint, gentle sounds, only to have our slumber intruded upon by a deafening tempest. And then, when the storm ends, we are delivered to the tranquillity from whence we came.

Is the decent to LV223, and all the horror that occurs there, somebody’s horrible nightmare? For Chopin, a soothing daydream quickly turned sour and the heavy rainfall led to imagined drowning, death and the loss of that which was most precious to him. But, as harrowing as these thoughts were, they were just thoughts. No ill came to any of the characters who were imagined to be under threat. Is it at all possible that the scenes framed by Chopin’s Raindrops are just the product of a character’s subconscious?

Well, yes, it is possible, but it would seriously undermine the integrity of the film. The nightmare, to me, is not literal; nobody is sleeping. The horror is just so incredible that the characters wish it were all a dream. The events unfolding are authentic, within the fictional reality of Prometheus. Giger’s nightmarish ideas have haunted this universe since it (chest) burst onto the scene in 1979. This world has been real now for over 30 years and I don’t think Ridley Scott wants us to wake up just yet.

Could it be possible that Scott believes this music has the power to invoke a dream-like state? Perhaps the irrational nature of its creation, encoded within its notes, casts a spell that might help us suspend our disbelief? I doubt it, but it is an entrancing piece that perfectly mimics the slow, melodic drift into sleep. It certainly doesn’t discourage a hypnotic state.

All of the above warrant its use, but I think there’s something deeper to be found here. Something to support the argument being put forward by Prometheus. Given the circumstances that led to the creation of Chopin’s composition, I believe that it has been selected to serve a higher purpose.

The music is a subconscious translation of the mesmerism of a Balearic storm; an involuntary reaction to its rhythm; the tapping of feet to unnoticed percussion. As he daydreams, Chopin is unaware that the music is not emanating from within, but from without. It’s not the product of free-will, but of external ‘programming’. His thoughts are being given to him.

And, as is often the case, this illusion of free will is encouraged by the ego. Chopin is horrified at the suggestion from George Sand that he has subconsciously imitated the pattern of the rainfall upon the roof. Of course, that could not have been the case, the implication is no good for the ‘soul’. It’s a masterpiece, of that there’s no doubt, but to ensure a sense of achievement, Chopin insists the work is the result of his own creative abilities. Attributing its creation to the weather outside would diminish his own genius and render him nothing more than an instrument of nature.

“Vanity is the quicksand of reason.”

– George Sand

The conclusion to be drawn is, therefore, that the director wishes to frame the dark discovery made by the Prometheus expedition as a nightmare. A nightmare inspired by the twisted art of Giger as it brings to life an evocative vision of how the myths of our ancient ancestors might have played out in the Alien universe. It’s a comment on the invariably unrecognised inspiration for human thought. Whether or not he would ever admit it, Chopin’s beautiful prelude speaks to us about how it is our thoughts emerge from the depths of our subconscious. Inspiration, as with all things, is at the mercy of the fundamental laws of the universe. Inspiration, like all thought, is the consequence of a cause not of its own making. Only supernatural forces have the power to create ex nihilo. All thought, and all existence, is the reverberation of a fundamental first cause; the truth. The Logos.

“Art for the sake of art itself is an idle sentence. Art for the sake of truth, for the sake of what is beautiful and good — that is the creed I seek.”

– George Sand

Chopin ‘chose to believe’ that he was in control of the music, when in fact, the music of nature was in full control of him.

Fanwank

LikeLike

As articulate as ever I see. This behaviour might net you brownie points in front of your fellow trolls on the [other website], but here it just makes you look uncouth. And a bit stupid, really.

LikeLike

“We have to wait for the final bars of the masterpiece, which are only heard once the blood curdling scream of the recently hatched xenomorph eventually fades into the blackness preceding the credits.”

The pseudo-xenomorph was goofy. Its appearance was a groan-inducing cliche. Did you seriously find it blood curdling?

“The heavy, stirring mid-section of the composition, the dark, chaotic, affecting nightmare that Chopin so eloquently captures in C-sharp minor, is never heard during the film. It is, instead, substituted by the ordeal we vicariously experience during the ill-fated mission undertaken by the Prometheus crew. This is intentional.”

Ill-fated? I thought you said the mission was designed to fail.

The intentions of the film makers created the deaths of the crew. It was formulaic slasher corporate movie making.

“What is the significance of this wonderful piece of music? Its calm, pleasant tone doesn’t appear to fit the overall feeling we get from Prometheus. Is it out of place? Or does it tell us something?”

Using a piece of classical music is part of the Alien formula.

In Alien, it was the first movement (adagio) from Howard Hanson’s 1930 “Symphony No. 2, Romantic”.

In Alien 2, it was references to Gayane’s Adagio from Aram Khachaturian’s Gayane ballet suite.

In Alien 3, the opening track vocals were Agnus Dei from the Catholic Mass.

In Alien 4, it was the aria “Priva Son D’Ogni Conforto” from George Frideric Handel’s opera Giulio Cesare.

In Alien 5, it was Frederic Chopin’s Prelude, Op 28, No. 15.

It’s a formula. Nothing more, nothing less.

LikeLike

Are you ready to have an honest discussion? Let’s see. Once you’ve read my thoughts regarding your non-argument, demonstrate some integrity and this discussion will continue. Any more of your petty, goalpost shifting nonsense and I’m afraid I’ll have no option but to ignore you here too.

We both know this isn’t going to be a very long conversation, but you can alter its fate by surprising me and being polite.

Remember, by posting here you have already admitted to wanting to discuss this film with me, and by not responding to you on [the other site] I have shown you that I have no such need. Any pretense that this isn’t the case will be seen as evidence of you having a bruised ego.

“The pseudo-xenomorph was goofy. Its appearance was a groan-inducing cliche. Did you seriously find it blood curdling?”

Because it’s a cliche within the context of an Alien film, the scream no longer makes our blood curdle. This is why Scott chose not to make yet another film where the xenomorph is the primary antagonist; it’s been done to death, and we’re desensitised. This is why he’s happy to destroy his child; the familiarity has bred contempt, and it’s the source of his misopedia.

Why do I describe it as blood curdling? Imagine yourself somewhere, anywhere other than somewhere where the wildlife is kept from hurting you by fences or cages, or a TV screen, and you heard that noise. Yes, it’s blood curdling.

“Ill-fated? I thought you said the mission was designed to fail.

The intentions of the film makers created the deaths of the crew. It was formulaic slasher corporate movie making.”

I have never said it was designed to fail. What I have implied is that it isn’t planned by Vickers with any concern for its success. She doesn’t think the mission is worthwhile because she doesn’t believe in Holloway’s thesis and she doesn’t want her father to find immortality. Hence her surprise at the sight of a dead engineer and her ‘a king has his reign’ speech.

Weyland, Shaw and Holloway certainly planned their part of the mission aiming for success.

So yes, ill-fated. Most everybody died, even the person that didn’t take it seriously, so yes, ill-fated. The mission ended badly. That’s the definition of ill-fated.

“Using a piece of classical music is part of the Alien formula.”

Yes, well observed. You’re clearly an Alien franchise fan. Now, do you think the specific choice is irrelevant? How do they choose which piece to play? Is it random?

So, are those questions all you have to contribute? Give me a sign that you’re genuinely interested in meaningful conversation. What are your thoughts on why Prometheus uses Raindrop? What are your thoughts on the reasoning I have applied to Scott’s choice? Could I be right? And if you think I’m wrong, why?

If my analyses are so poor, and my use of language so awful, as you’ve previously claimed, why are you here commenting?

LikeLike

“Are you ready to have an honest discussion? Let’s see. Once you’ve read my thoughts regarding your non-argument, demonstrate some integrity and this discussion will continue. Any more of your petty, goalpost shifting nonsense and I’m afraid I’ll have no option but to ignore you here too.

We both know this isn’t going to be a very long conversation, but you can alter its fate by surprising me and being polite.

Remember, by posting here you have already admitted to wanting to discuss this film with me, and by not responding to you on [on the other website] I have shown you that I have no such need. Any pretense that this isn’t the case will be seen as evidence of you having a bruised ego.”

The problem is that you keep posting on [the other site] with a self-congratulatory tone. You say no-one has any answers for you, yet whenever you get your answers you put those people on ignore.

The original bone of contention for you was Prometheus’ status as a piece of art. I asked you about who made the film, and you put your head in the sand.

You won’t admit that Prometheus was made by a corporation, and that Ridley Scott et al were hired hands. The implications for the artistic intention are obvious. Executives and accountants don’t have any artistic statements to make about our humanity.

There was never any moving of goalposts. The initial misunderstanding was yours, and the refusal to be honest was also yours.

You bring your website writings to the [other website] and ignore the counterarguments. I was curious to see if you would ignore the arguments brought directly to your website. This is a one time deal. I won’t be hounding your other articles.

“Because it’s a cliche within the context of an Alien film, the scream no longer makes our blood curdle. This is why Scott chose not to make yet another film where the xenomorph is the primary antagonist; it’s been done to death, and we’re desensitised. This is why he’s happy to destroy his child; the familiarity has bred contempt, and it’s the source of his misopedia.

Why do I describe it as blood curdling? Imagine yourself somewhere, anywhere other than somewhere where the wildlife is kept from hurting you by fences or cages, or a TV screen, and you heard that noise. Yes, it’s blood curdling.”

So I have to imagine that I’m not watching a movie. Do I have to imagine a realistic looking creature? The creatures in Prometheus all look fake, and this one is the worst. It looks like a Muppet baby version of the original xenomorph, with its rubber glove hands and cute little head.

Some movies have animal noises that do make my hairs stand on end. I don’t have to imagine that I’m in the wild. Good sound design will create a reaction. Prometheus did not have good sound design.

“I have never said it was designed to fail. What I have implied is that it isn’t planned by Vickers with any concern for its success.”

Hmm…

“In fact, if we read between the lines, there’s a subtle suggestion that they’ve been hired to fail.

Vickers says “To those of you I hired personally…”

Later, we see that she’s a sceptic and did not expect to find anything there. It can be assumed that she didn’t take the mission seriously and therefore didn’t invest much money or effort in recruiting.”

Designed to fail, not planned to succeed… splitting hairs.

Either way, you can hardly call the mission ill-fated. That suggests it was done with the best of intentions and went awry due to bad luck.

“[Vickers] doesn’t think the mission is worthwhile because she doesn’t believe in Holloway’s thesis and she doesn’t want her father to find immortality. Hence her surprise at the sight of a dead engineer and her ‘a king has his reign’ speech.”

I’ve heard this excuse from a lot of Prometheus fans. The problem with your logic is that the incompetent crew put her life in danger, and eventually got her killed. Why on earth would she plan to kill herself by proxy?

And if she was suicidal, why run from the ship?

Ah, maybe that’s why she ran in front of the falling ship. She did want to die after all.

So why was Vickers suicidal?

“Weyland, Shaw and Holloway certainly planned their part of the mission aiming for success.”

Really? Then how did things go so badly?

I guess Shaw and Holloway could just be really bad at planning, but isn’t Weyland meant to be a trillionaire? Isn’t planning kind of his thing?

“So yes, ill-fated. Most everybody died, even the person that didn’t take it seriously, so yes, ill-fated. The mission ended badly. That’s the definition of ill-fated.”

Ill-fated means bad luck. None of the characters died from bad luck. They died from hugging alien snakes, turning their back on zombies, asking to be set on fire, crashing their ship on purpose, and so on.

At best they died from sheer idiocy, but really it’s just transparent hack writing. It’s no different to stoned teenagers being picked off by Jason Voorhees.

“Using a piece of classical music is part of the Alien formula.

Yes, well observed. You’re clearly an Alien franchise fan. Now, do you think the specific choice is irrelevant? How do they choose which piece to play? Is it random?”

I’m not a big fan of the franchise. I love Alien 4, and Alien 3 is great too.

Yes, the specific choice is irrelevant to the themes of the movie. Remember the corporate nature of the film? There is no theme. They followed the formula, kept it vague, and hoped people would swallow it.

“So, are those questions all you have to contribute? Give me a sign that you’re genuinely interested in meaningful conversation. What are your thoughts on why Prometheus uses Raindrop? What are your thoughts on the reasoning I have applied to Scott’s choice? Could I be right? And if you think I’m wrong, why?

If my analyses are so poor, and my use of language so awful, as you’ve previously claimed, why are you here commenting?”

You’re just blustering now. I’ve already answered those questions.

Prometheus uses Raindrop because it’s part of the Alien formula to include a classical piece.

That specific piece could have been chosen for any number of reasons. Maybe it’s a personal favourite of the editor, it doesn’t matter. It has nothing to do with Prometheus.

Your reasoning is not in fact reasoning. You are using Prometheus as a springboard for your own writing and ideas. That’s fine, nothing wrong with expressing yourself. But it doesn’t connect with the film. You’re just creating more fiction.

I mean, when I write a poem, I don’t apply reasoning. I just write something I feel. Why are you asking for reason? I’m not sure why you would want to intellectually deconstruct a piece of art, but if that’s your intention, you must be honest about the facts of the artwork. You can’t pretend Prometheus is a painting, or runs for 17 hours. You can’t pretend it’s in Chinese or stars Sonam Kapoor. And you can’t pretend that it was made by artists instead of business people.

Imagine that Chopin has resonance to the narrative. Feel that it’s true. That’s your trip, and that’s fine. But there’s no reason to it.

LikeLike

I’m actually convinced that you truly believe you’ve provided answers with this comment of yours. I can tell you that you haven’t. Your comments are quite frankly nonsense. It’s yet more lies (you said Prometheus wasn’t a film when I stated that film is a collaborative art form) and you’ve simply shifted the goal posts once again. You are incapable of accepting when you’re wrong. Why would anybody spend their time having a conversation with somebody so dishonest? What’s to be gained? My irritation? Congratulations, you’re as powerful as a gnat.

I don’t know what you get done with your day, but I try to spend mine productively. I try not to waste any of it with people like you.

You had your chance. It went precisely as I predicted. You’re free to post here – I won’t stop you – but I’m sorry, I won’t respond.

LikeLike

Another great read Movie Dude. Im always keen to read your thoughts on Prometheus because you always give me something new to think about. I didnt know there was anything special about the music until now. Your analysis makes perfect sense and supports your other comments about programming.

Dont worry about the trolls. The poster above is just ignorant. Dont let people like thst put you off writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, MKY. Your comment is greatly appreciated.

Trolls are powerless. All you need do is ignore them. It’s a simple as that!

LikeLike